The recent 12-day Iran-Israel war has reignited discussions about Iran’s nuclear program. Was it ever genuinely peaceful? How significant is Russia’s role in supporting Iran’s nuclear ambitions? Are the Iranians capable of building a bomb right now? T-invariant discussed these questions with Dmitry Kovchegin, author of a publication by the Israeli Institute for National Security Studies on Russian-Iranian nuclear cooperation.

T-invariant: Iran consistently claims its nuclear program as peaceful. Was it ever truly so?

Dmitry Kovchegin: Iran’s nuclear program was peaceful only in its early days, under the Shah. In the 1970s, the United States assisted Iran with a research reactor, and Germany was constructing the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant. But then came the Islamic Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War. After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, when the ayatollahs revived the nuclear program, its objectives shifted dramatically. David Albright, author of the most comprehensive book on the subject, Iran’s Perilous Pursuit of Nuclear Weapons, cites Ali Khamenei — then not yet the Supreme Leader — who argued that developing nuclear weapons was essential to counter external threats.

T-INVARIANT PROFILE

Dmitry Kovchegin was born in 1977. He graduated from the National Research Nuclear University MEPhI (Moscow Engineering Physics Institute) with a degree in “Physical Protection, Accounting, and Control of Nuclear Materials and Non-Proliferation.” In 1999, he interned at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies’ Center for Nonproliferation Studies in Monterey, California. He has served as a research fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University and as an independent consultant for the PIR Center’s Expert Council (a Moscow-based think tank focused on arms control and nuclear non-proliferation).

T-i: So, the goal was to build a bomb to counter Iraq?

DK: Partly, but primarily it was aimed at deterring the United States and Israel as a tool of foreign policy.

T-i: In your research, you noted that Iran initially aimed to produce five bombs by 2003 but failed to achieve this goal.

DK: I wouldn’t say the program in the late 1990s and early 2000s was a complete failure. It included all the critical components required to develop nuclear weapons. By 2003, the program began attracting too much attention from the international community. Iran, facing increasing international pressure, chose to scale back its activities. By then, Iran had made substantial progress. Since then, and possibly with a pause during the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) — the first nuclear deal with the U.S. — Iran has been engaging in a cat-and-mouse game with the international community. It has aimed to avoid military confrontation while maintaining a threshold nuclear capability, pursued with varying intensity.

T-i: How much of this progress was Iran’s own achievement, and how much relied on foreign assistance?

DK: The first design of an explosive device that came to Iran was Pakistani. The leaks of nuclear technologies from Pakistan are associated with nuclear scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan. Regarding Soviet-era technologies, it’s more accurate to focus on the actions of specific individuals. The most well-documented case involves physicist Vyacheslav Danilenko. He worked at the All-Russian Scientific Research Institute of Technical Physics (VNIITF) in Snezhinsk, one of the Soviet Union’s two nuclear weapons laboratories. After the USSR’s collapse, he retired and moved to Kyiv but later ended up in Iran. Officially, he was involved in creating synthetic diamonds, but the physics of diamond compression is similar to the compression of nuclear material in a bomb. China helped establish the nuclear technology research center in Isfahan but likely did not directly contribute to Iran’s military nuclear program. North Korea aided in the development of ballistic missiles.

Top news on scientists’ work and experiences during the war, along with videos and infographics — subscribe to the T-invariant Telegram channel to stay updated.

Notably, Iran’s nuclear program has never been heavily dependent on any single country, whether Russia, China, or North Korea. From the outset, Iran aimed for self-sufficiency, ensuring it could develop everything independently. If Iran decides to build a nuclear weapon, it will likely rely on the knowledge and technologies it has already mastered rather than scrambling for foreign assistance. However, Iran may continue to leverage foreign expertise and technologies, obtained through various channels, to enhance its capabilities over time.

T-i: But Iran did receive some assistance from Russia, didn’t it?

DK: Russia and Iran have collaborated in the nuclear field since the early 1990s, but there is no evidence of support for Iran’s weapons program. In August 1992, Iran was the first country to sign intergovernmental agreements with the newly independent Russia on peaceful nuclear energy cooperation and the construction of a nuclear power plant. These agreements also envisioned potential collaboration on research reactors, personnel training, medical isotope production, and joint research. However, actual cooperation didn’t begin until 1995, partly due to Russia’s concerns about Iran’s nuclear ambitions. A 1993 report Russian Foreign Intelligence Service report raised concerns about Iran’s military nuclear research. In contrast, the 1995 report by the same service, published that year, expressed no concerns and questioned U.S. claims about Iran’s nuclear weapons program.

The initial agreements between Russia and Iran in 1995 envisioned cooperation and personnel training in sensitive areas. For example, there was a provision for the supply of uranium enrichment technology using gas centrifuges. The United States then intervened, preventing Russia from supplying Iran with uranium enrichment technology. Russia then prioritized its relationship with the U.S. and they limited cooperation to the field of nuclear energy. Russia completed the construction of the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant and trained its staff.

T-i: Did Russia manage to transfer any sensitive technologies to Iran before the U.S. intervened?

DK: Certain organizations likely exploited gaps in Russia’s export control system to work with Iran independently. For instance, the Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology and the Research and Design Institute of Power Engineering, led by Yevgeny Adamov (later head of Russia’s Ministry of Atomic Energy), reportedly collaborated with Iran on designing a heavy-water reactor, which could potentially produce weapons-grade plutonium. Both organizations faced U.S. sanctions, which were later lifted after the cooperation ceased.

T-i: The heavy-water reactor in Arak was one of Israel’s targets. Reports suggested it could produce weapons-grade plutonium.

DK: The Arak reactor was never completed. Heavy-water reactors operate on natural uranium fuel. Their design and fuel type allow them to produce weapons-grade plutonium. Under the first nuclear deal the Arak reactor’s design was altered to prevent weapons-grade plutonium production. Under that deal, Iran’s heavy water stockpile was shipped to Russia.

T-i: So, in addition to a uranium-based bomb, was Iran also pursuing a plutonium-based one?

DK: Iran primarily focused on the uranium track. The uranium and plutonium tracks diverge early on. You can’t simply swap one for the other. Iran might have explored plutonium-related work as part of building broader nuclear expertise, possibly with military applications in mind.

Up-to-date videos on science during wartime, interviews, podcasts, and streams with prominent scientists — subscribe to the T-invariant YouTube channel!

T-i: Some key figures in Iran’s nuclear program were trained in Russia. Reports indicate that twenty scientists were killed during the 12-day war. Not all their names have been released, but some are known to have studied in Moscow.

DK: Yes, for example, Mohammad Mehdi Tehranchi earned his dissertation in 1997 at the Institute of General Physics of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He later worked on implosion techniques for Iran’s nuclear program. Did Russia know he would later work on an atomic bomb? I think it’s likely that he had no such plans at the time. He was just a young physics graduate student back then. From 1994 to 2000, while I was studying at MEPhI, foreign students from various countries, including Iran, were enrolled.

T-i: At the same time, in 1998, Abdolhamid Minouchehr defended his dissertation at MEPhI, another scientist killed by Israel during the 12-day war, a nuclear physicist and engineer, the dean of the Faculty of Nuclear Engineering at Shahid Beheshti University. Did you know him?

DK: Public records indicate that his academic supervisor was Vyacheslav Khromov, who led the Department of Theoretical and Experimental Physics of Nuclear Reactors at MEPhI. I was also studying in that department, but we weren’t acquainted.

Back then (1995 — T-i), Russia and Iran signed an agreement for the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant, which needed experts in reactor operations. Those skills could potentially be applied in a military nuclear program, but I don’t believe Russia intended to support Iran’s weapons program through this partnership. Incidentally, Iranian students could study physics not only in Russia but also in Europe and the United States.

T-i: One more nuclear scientist killed during the war, Seyyed Amir Hossein Feghhi, worked at CERN. That’s unrelated to nuclear weapons, right?

DK: This is an example of how a career path might unfold. Students usually begin with general physics. Then they move into a specialized field. I’d say nearly all, if not all, went abroad solely to study, not with any premeditated aim of working on nuclear weapons. Looking at the Soviet experience, the transition to military work typically occurred in later years of study or after graduation, when top candidates received an offer they couldn’t refuse — in every sense of the phrase. I suspect Iran’s program recruited individuals similarly.

T-i: Now that Iran has its own expertise, is studying abroad still necessary?

DK: I believe Iran is fully capable of training its own nuclear specialists. Iran likely has hundreds of young experts. Naturally, some will be eager to replace the scientists killed by Israel. However, these new scientists don’t have the needed experience, and filling those gaps quickly will be tough. The twenty scientists were killed during the war were the elite, such as Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, the leader of Iran’s nuclear weapons program since the 1990s, who was assassinated in 2020.

T-i: Based on your assessment, can Iran build a bomb right now?

DK: Iran’s nuclear program is less advanced than Russia’s or the United States’, but they have sufficient knowledge to create a functional nuclear explosive device. There are two distinct challenges: first, building a nuclear explosive device; second, creating one that can be delivered by a missile, survive high-speed flight, and detonate precisely when and where intended. I believe Iran has long been capable of building a basic nuclear explosive device. If they haven’t yet solved the second challenge, they’re at least close.

T-i: Is there a chance Russia could assist Iran at this final stage?

DK: Since the early 1990s, at least until the collapse of the first nuclear deal (JCPOA), Russia limited its cooperation with Iran to nuclear energy. This likely continued until Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. I’m concerned that Russia could provide dual-use technologies — those not directly tied to a military nuclear program but legally transferable under certain conditions. Such technologies could enhance Iran’s nuclear program overall. Russia is a global leader in uranium enrichment technologies, and cooperation in this area could significantly benefit Iran.

As for the nuclear weapons program itself, I doubt Iran would directly ask Russia for help with specific gaps. Requesting assistance exposes vulnerabilities, and trust between Iran and Russia, despite recent warming of relations, remains limited. Similarly, Russia is unlikely to share its most sensitive information, as it underpins its defense capabilities, and there’s no guarantee Iran wouldn’t leak it to foreign intelligence or use it against Russia.

T-i: Russia’s response during the Iran-Israel war significantly disappointed Tehran. Will this affect nuclear cooperation?

DK: I don’t think so. Negotiations with the U.S., involving both Russia and Iran, regarding nuclear cooperation are likely to have a far greater impact. In any case, Russia won’t abandon cooperation in nuclear energy. Russia is expanding the Bushehr plant and plans to construct another nuclear power plant in Iran. The U.S. won’t object, as this cooperation poses minimal risks to non-proliferation. The fact that Bushehr wasn’t targeted during the war suggests neither the U.S. nor Israel sees it as a threat.

T-i: Russia has offered, as part of a new deal, to store Iran’s enriched uranium. Hasn’t something similar happened before?

DK: Under the JCPOA, Iran shipped enriched uranium and heavy water to Russia. That uranium is still in Russia. In theory, Iran could request that Russia to use it for fuel production for Bushehr. Ironically, the current U.S. administration is pursuing a deal similar to the one Trump exited, albeit with modifications. It was designed by experts and included measures to address concerns about Iran’s nuclear program.

T-i: But that deal faced sharp criticism. Iran concealed facilities from the IAEA, and partial sanctions relief allowed it to build missiles and fund terrorist groups from Hamas to the Houthis.

DK: The deal wasn’t perfect but it offered a compromise that benefited all parties. It could have been refined rather than scrapped. The current situation is far less certain than before the deal’s collapse. The IAEA no longer has access to internal information. Information about Iran’s uranium stockpiles and equipment is limited. In some ways, things are even murkier than it was before the Israel-Iran war.

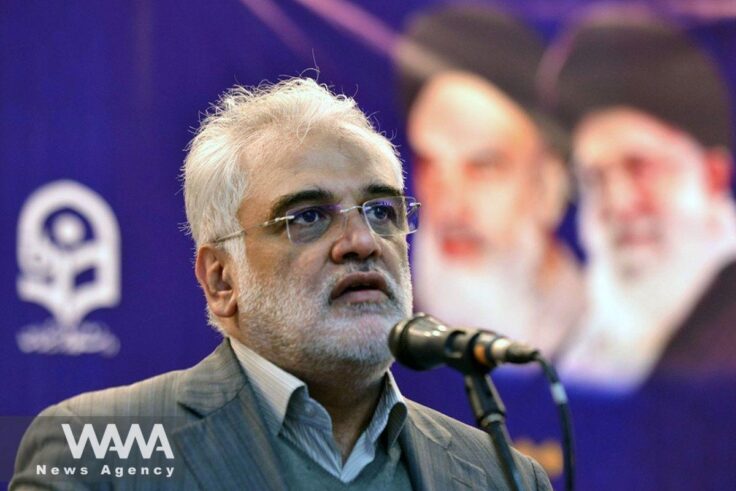

Photo of Dmitry Kovchegin in the collage illustration: Efrat Eshel.